If 2024 shook Bangladesh, 2025 pushed it closer to the edge. What should have been a year of stabilisation after the mass uprising instead unfolded as one of deepening disorder, marked by political drift, unchecked violence, economic strain and a steady erosion of public safety. By the end of the year, the state appeared weaker, society more fractured and institutions increasingly unable to impose authority.

At the heart of this turmoil stood a lacklustre interim government that increasingly appeared overwhelmed by events. Despite the presence of the army, police and other forces, it struggled to contain instability. Violent mobs gained ground, human rights concerns intensified and confidence in governance waned. The cumulative effect was a nation trapped in transition, uncertain not only about its political future but about its ability to restore basic order.

With the national election now just 42 days away, expectations have narrowed to a single hope: that an elected government, regardless of its composition, will bring an end to prolonged uncertainty and allow 2026 to begin as a year of consolidation rather than crisis.

The death of BNP chairperson and former prime minister Khaleda Zia on 30 December was a final shock for the nation, yet it briefly united a deeply divided society in collective mourning, which many observers see as a positive sign.

The return of Tarique Rahman, Khaleda Zia’s son, after a prolonged exile is also seen as a positive development, with many expecting it may help create a calmer political atmosphere ahead of the election.

Whether the hope and aspiration are realistic, however, remains an open question.

A transition that slipped

The turbulence of 2025 was inseparable from the aftermath of 2024, when mass protests forced long-time prime minister Sheikh Hasina from power, ending her authoritarian rule. The uprising dismantled an entrenched political order but left behind a vacuum that proved difficult to manage.

The interim government led by Nobel laureate Muhammad Yunus entered office with credibility abroad and public goodwill at home, but limited capacity to enforce authority. Instead of restoring control, the state appeared reactive as pressures mounted from multiple directions.

Political tensions deepened after Sheikh Hasina was tried in absentia by the International Crimes Tribunal and sentenced to death for alleged crimes against humanity. While the verdict was welcomed by many as overdue accountability, it further sharpened divisions at a time when political restraint was already in short supply.

Reign of the mob

The most destabilising feature of 2025 was the surge in mob violence. Rights groups recorded at least 197 deaths linked to mob attacks, highlighting how rapidly the rule of law weakened in the absence of effective enforcement. These incidents were often fuelled by political rivalries, religious tension and rumours amplified through social media.

Minority communities were also targets. Attacks on Hindu homes in Gangachara and lynchings such as the killing of Dipu Chandra Das exposed rising intolerance and the inability of authorities to prevent collective violence.

The crisis extended beyond physical attacks. Two major newspaper offices were assaulted by violent mobs, marking a dangerous escalation against the media. These incidents sent a stark signal: institutions meant to hold power to account were themselves becoming targets, further shrinking the space for scrutiny and public debate.

Alongside mob violence, reports of extrajudicial killings, harassment of journalists and intimidation of activists reinforced concerns that rights protections were weakening even as security deployments increased.

Economic stress, industrial failure

Political instability carried significant economic costs. Growth slowed, business confidence faltered and households faced rising pressure. Industrial disasters compounded these challenges.

A factory fire in October once again exposed chronic safety failures, while the massive blaze at Dhaka’s airport cargo terminal destroyed ready-made garment exports worth an estimated USD 1 billion. The loss disrupted supply chains and underscored how vulnerable the country’s key export sector had become.

Workplace safety deteriorated sharply. More than 1,190 workers were reported killed during the year, particularly in informal sectors where regulation remains weak. These deaths highlighted structural neglect rather than isolated accidents.

A society under strain

Beyond politics and economics, 2025 revealed deep social distress. The Magura child rape case, in which an eight-year-old victim died, triggered nationwide protests and renewed scrutiny of law enforcement and child protection systems.

More broadly, fear became a defining feature of daily life. Minority communities, journalists, women and ordinary citizens increasingly felt exposed, relying less on state protection and more on personal caution. Social cohesion weakened as uncertainty and anger replaced confidence.

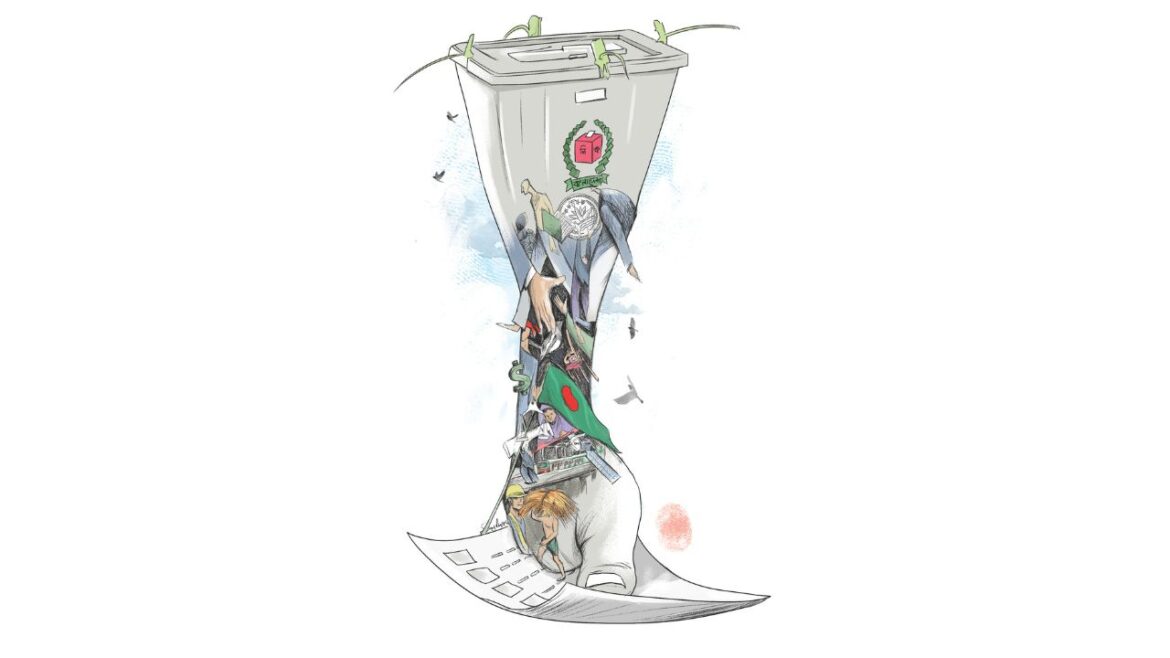

Waiting for the ballot

As the year 2026 begins, the approaching election has become the focal point of national expectations. For many, it represents a necessary step toward restoring legitimacy after prolonged interim rule.

There is also a clear undercurrent in public sentiment: a rejection of a return to personalised, unaccountable rule. The demand is less about personalities than about preventing another concentration of power that weakens institutions and sidelines dissent.

What is clear is that 2025 exposed the cost of prolonged transition without authority. The challenge for 2026 will not merely be forming a government, but rebuilding the state’s capacity to govern, protect and hold itself accountable after a year that brought Bangladesh dangerously close to the margins.