In one go, it is impossible to explore the length and breadth of a country—regardless of how large or small its geographical area may be. This is true even for a country like Bhutan, where nature is stunning, heritage is rich, and the public perception of prosperity is not confined to economic growth alone. Here, prosperity is less about gross domestic product (GDP) and more about gross national happiness (GNH).

While GDP measures a nation’s economic output, GNH is a holistic alternative pioneered by Bhutan. It assesses overall well-being by incorporating psychological, environmental, cultural, and governance factors beyond mere financial indicators, aiming for sustainable and equitable development rather than pure economic growth. Essentially, GDP asks: “How much wealth are we making?” while GNH asks: “Are we living well, sustainably?”

Ideally located in the heart of the national capital, Thimphu, Simply Bhutan is a highly interactive living museum that offers an immersive introduction to traditional Bhutanese life. A visit to Simply Bhutan can serve as a rewarding prelude for tourists, offering a glimpse of what to expect from this landlocked Himalayan kingdom—the “Land of the Thunder Dragon”—its deep-rooted Buddhist culture, dramatic landscapes of monasteries and fortresses, and its commitment to GNH by balancing tradition with modernity.

During my business trip to Thimphu earlier this year, when the cool February breeze was pleasant and the Bhutanese sky wore an unusually vivid blue, I stepped into Simply Bhutan one afternoon and was greeted with a shot of ara (rice wine). A guided experience allowed me to explore various cultural aspects firsthand—from dressing in traditional Bhutanese attire and learning how ara is distilled, to being introduced to dragon masks of different denominations, traditional kitchen utensils, culinary practices, and even dancing to the tunes of Bhutanese folk songs sung by local artists.

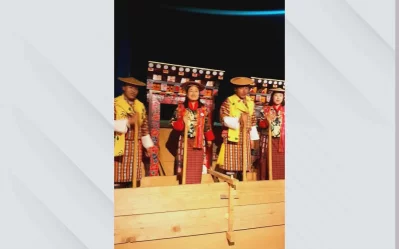

As a novice, I also tried my hand at archery and khuru (a local dart game), observed the construction techniques of traditional Bhutanese houses, and learned how Bhutanese preserve dried chili peppers—a major component of their cuisine. Near the museum entrance, artists performed a welcoming song accompanied by a dance choreographed to depict the process of rice distillation used to make high-quality ara.

Further inside the museum, a wide array of artefacts is on display, allowing visitors to witness and admire the artisan skills of the Bhutanese people, particularly the intricate woodwork seen in traditional kitchen utensils.

Simply Bhutan is a cultural conservation project dedicated to preserving Bhutan’s heritage while creating employment opportunities for local youth. The museum’s architecture reflects traditional Bhutanese design, featuring repurposed timber, doors, window frames, and other materials salvaged from demolished houses. This sustainable approach ensures that Bhutan’s architectural heritage remains alive for future generations.

Later, I enjoyed performances of traditional songs and dances that have been passed down through generations and are now performed by young Bhutanese artists with remarkable skill and eloquence. They also encouraged visitors to participate in a few dance steps, which were simple yet graceful.

Once the dance and musical performances concluded, I was offered a traditional Bhutanese dinner. It was sumptuous and deeply satisfying, to say the least. While Bhutanese cuisine bears influences from neighbouring countries such as India, China, and Nepal, its defining hallmark is spiciness, with chilies at the heart of nearly every dish.

Datsi—a locally available cheese with a texture and taste similar to feta, but without the salt—is used abundantly in many dishes. The Bhutanese diet is rich in meat, poultry, grains, and vegetables. Both dried and fresh chilies are used generously, either to spice up stew-like curries or as the main ingredient, usually accompanied by steamed rice, the primary source of carbohydrates. My personal favourite is red rice, valued for its nutritious qualities, delicate texture, and nutty, earthy flavour—especially when served with tender chicken pieces stir-fried with bell peppers.

When I first noticed rows of dried chili peppers hanging along the sidewalls inside the Simply Bhutan museum, I could already imagine how central chilies must be to Bhutanese cuisine. Later, I discovered that chilies are almost a staple in many Bhutanese delicacies. Central to Bhutanese cuisine, the humble chili—known locally as ema—is not merely a spice but a defining feature of the nation’s gastronomic identity.